Unsung Heroes

Small-scale farmers preserve seed-saving traditions

By Shane Maxson

A seed farm is an amazing sight at harvest time as plants embrace their wild form. Brassicas like arugula and turnips transform into monstrous creatures shooting flower stalks skyward like towering monoliths; peas and beans hang bone dry on withered vines, while squash and pumpkins sprawl lazily across the ground in every direction.

Growing seeds is similar to growing fresh vegetables. But rather than harvesting ripe fruit in the spring or summer, farmers leave the produce on the vine until fall when the seeds dry out, or bring wet fruits like tomatoes inside to separate the seeds from the gooey pulp.

Seed farmers are the unsung heroes of the garden world, and their work is often hidden from casual home gardeners who flip through seed catalogues or pick up seed packets each spring. When asked where vegetables come from, most people would answer without hesitation: a farm. When asked where seeds come from, the response isn’t quite as forthcoming.

The vast majority of agricultural and garden seeds are grown on a scale that would’ve been unimaginable to our forebears. Picture massive greenhouses and hundreds of acres of seed crops grown on large farms on the West Coast of the United States, as well as in China, France, Brazil, and India, where teams of farmers grow thousands of varieties of seeds for this multi-billion-dollar industry.

It’s nearly impossible to trace the provenance of seeds grown on large-scale farms because international seed companies rarely disclose the locations of their farms. Yet some Southern Appalachian seed companies are leading a resurgence of local farmers who grow seeds on a smaller, more transparent scale here in the mountains.

Kim Bailey is a seed farmer in Western North Carolina who grows bean, pepper, and milkweed seeds. Her farm, Milkweed Meadows, is a waystation for monarchs on their annual migration between the United States and Mexico. Bailey’s love of nature-based education catapulted her into the world of seeds.

“It began as a hobby,” Bailey says. She was working as an environmental educator and needed seeds for pollinator gardens. “When I moved from Georgia to North Carolina in 2014, I dreamed of starting a farm-based business, so I began with what I knew best—growing milkweeds and other plants that attract pollinators.”

Bailey found an outlet for selling her milkweed seeds in Asheville seed company Sow True Seed. “Because of Sow True Seed’s commitment to working with local growers, I have been able to turn my hobby into a small business,” Bailey says.

Sow True Seed sells organic, heirloom, and “open-pollinated” seeds which grow into plants that reproduce through natural pollination. Open-pollinated seeds are quite different from hybrid seeds,which are bred by humans to display traits from two distinct varieties. Seeds saved from hybrid plants will not maintain their characteristics when planted the following season because the genetics of the hybrid aren’t stable enough to reliably reproduce the same traits. For this reason, farmers and gardeners do not save hybrid seeds, and instead purchase them from seed companies year after year.

Locally grown, open-pollinated seeds have many advantages over seeds grown in other regions, says Sow True spokesman Chris Smith. “Open-pollinated means that within a given variety, let’s say a Cherokee Purple tomato, there is a relatively stable mix of genetics. When seeds are saved from fruit within that population, the seeds will grow ‘true to type.’” In other words, if saved correctly, this year’s Cherokee Purple tomatoes will produce seeds that result in nearly identical Cherokee Purple tomatoes when planted the following year.

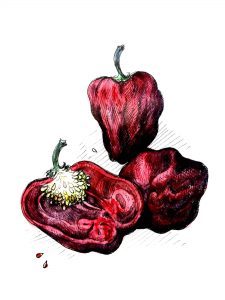

Bailey grows or trials over a dozen different vegetables for Sow True Seed, including Dark Pot Liquor Lima Bean, Cherokee Turkey Eye Pole Bean, and Criolla de Cocina Sweet Pepper. “My vegetable seed crops are grown in a garden plot that is under an acre in size,” Bailey says. “If you are growing on a small scale as I am, the start-up costs are not high. For example, instead of needing to purchase a greenhouse, I can use an indoor shelving unit and shop lights to start seeds early for transplanting into the garden after outdoor temperatures are warm enough.”

Growing fruit and vegetables for seed isn’t very different than growing them for food. “Growing seeds is easy—it’s what a plant wants to do,” Smith says. The main difference comes at harvest time and during pollination, when special precautions must be taken. “Preventing accidental cross-pollination can be a challenge,” he adds.

Cross-pollination is when two plants of the same species, but of different varieties, swap pollen. This is a huge problem for seed growers because they need their crops to have varietal purity. Imagine if your sweet corn was crossed with a corn that was bred for animal feed. That juicy corn on the cob wouldn’t be so juicy. Smith recommends that seed-saving novices start with tomato, bean, pea, and lettuce seeds. “These are four easy-to-grow crops that don’t readily cross-pollinate with each other,” Smith notes.

When growing crops that will cross-pollinate with each other, farmers take steps to avoid genetic contamination. “The seed company will require a certain ‘isolation distance’ in the seed grower’s contract,” Bailey notes. “This means you cannot grow one variety within a certain distance of another variety of the same species. Another way to keep seeds pure is to bag flowers of plants that are self-pollinating. I needed to do this last year for the okra seeds I produced because I knew one of my neighbors was also growing okra about half a mile away.”

While seed farming is not always fun and games, the process of cleaning seeds for storage and sale can sometimes be a bit of both.

“Seeds that are harvested when dry, such as cowpeas and beans, must be separated from the pods and chaff,” Bailey says. “Rather than hand-shucking each pod, I lay the dried pods out on a tarp and dance around on top of them. Once the seeds have been released, I pour everything out in front of a large fan. Since the seeds are heavier than the chaff, the wind from the fan blows away the debris, and I’m left with very clean seeds.” Then the seeds are packaged and sold by Sow True Seed the following spring, where they begin a new life in the hands of a local gardener.

Whether you are sowing seeds in your backyard, or digging into a vegetable ratatouille at a local restaurant, behind every vegetable there is a seed, and behind that seed stands a farmer. ◊◊

Shane Maxson’s work at natural food co-ops, on farms, and formally at Sow True Seed established his deep relationship to food. He currently focuses on local grain sourcing in craft beer through his work with Riverbend Malt House.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Local seed farmer Kim Bailey grows several vegetables for Sow True Seed, including Criolla de Cocina Sweet Peppers.

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.