The Whole Hog

The past and the future of livestock farming converge in Western North Carolina

By Beth Lassiter

It’s morning at Hickory Nut Gap Farm, about 14 miles south-east of Asheville in Fairview, and the hogs are enjoying life in the dappled light of the farm’s forested land, rooting, grunting, and giving each other playful nudges. Three employees begin to ease them out into the meadow, using the calls the animals recognize. Owner Jamie Ager stands in a patch of jewelweed watching them go.

“Food’s pretty spiritual,” says Ager. “We want to be connected to the food we eat. I think it’s really important that food is elevated beyond just a cost paradigm, to a point where there’s respect for the natural instincts of the animal. With pigs, it would be rooting and wallowing and doing what pigs like to do.”

Ager is one of a new generation of pig farmers—deeply knowledgeable about history, informed by recent trends, and looking forward to what he calls “a new agriculture.” This model considers human as well as hog welfare, connects consumers directly to producers, and is conducted with an eye to sustainability. And it is deeply rooted in North Carolina’s past.

More Hogs than People

There was an old saying that more hogs lived in the state of North Carolina than people. And while humans finally did surpass hogs in this last decade, with over 9 million hogs to about 10 million of us, there are still two counties—Sampson and Duplin—where hogs outnumber humans 29 to 1. In 2016, the state produced 4.15 billion pounds of pork, according to North Carolina State University, putting it second only to Iowa in hog production.

Much of that production takes place in the eastern coastal plain of the state, which offers abundant acreage for raising corn and soy, as well as for housing the hogs. In addition, according to the North Carolina Pork Council, the eastern region relies on its close proximity to processing plants, like those in Smithfield, Virginia. Not to be overlooked are the generations of hog farmers with know-how who long ago settled in that part of the state.

In the mid- and late-20th century, advances in technology changed the nature of hog production and led to the creation of large-scale operations. Asheville-based historian Mark Essig, author of Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig, describes it as “importing a Midwestern mode of intensively bred, intensively fed model to the South where there was cheap land, lax environmental regulation, and the lack of an organized labor force.”

Since then, the state has imposed regulations and introduced moratoriums on large facilities. Regulators were also forced to respond to the disastrous aftermath of Hurricane Floyd in 1999, when hog waste “lagoons” were breached and countless hogs were drowned. More recently, Hurricane Florence again caused lagoon breaches. Still, most pork sold in groceries comes from commercial operations producing the most affordable and plentiful product. In the west, the mountainous terrain never allowed pork operations to grow that large, and farms were more likely to produce tobacco, beef, or dairy. In 2005, though, the federal government began a buyout of tobacco farmers, and those farmers turned to other commodities that would allow them to keep their land and their way of life.

“We knew there was going to be a big shift and potential farm loss,” says Molly Nicholie, program director for the local food campaign at the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project, or ASAP. “So we were looking at what opportunities there were for farms to do other things.” One of those other things turned out to be pork.

Today, across the landscape of Western North Carolina, many small farms are tucked into small pastures and hollers where hogs are counted merely by the dozen. Of the 2,436 hog farms counted in a 2017 census of the state, more than 1,000 had just 24 or fewer hogs. And smaller operations are popping up statewide to cater to new markets, especially to consumers who are willing to pay a premium for meat raised and harvested in ways that may be more humane than mainstream agriculture. At the same time, many of those smaller farms are continuing the hog-raising traditions that determined the course of Asheville’s history.

Herding Hogs

For the small-time farmers and others who settled in Western North Carolina in the early 19th century, hogs helped them to get by. They were a reliable food source from the moment Europeans introduced them to the continent, easy to feed and keep, even on a hillside or in a holler. “There was essentially no cost to raising hogs if you were running them in the woods,” says Essig.

An early winter slaughter that was smoked, salted, or kept cool provided for most of the coming year. Mountain hogs were allowed to roam free for large portions of the year and fattened themselves on chestnuts, the food they most loved, making chestnut-raised pork a delicacy we can only now imagine. “If you were lucky,” Essig says, “you kept your own pig. If you were really lucky, you kept your own pig and a second one to sell.”

The statues in Pack Square celebrate an important chapter in the area’s history, when thousands of hogs were driven through downtown Asheville every year.

Essig became interested in the history of the pig after moving to Asheville and seeing the porcine statues in Pack Square that celebrate an important chapter in the area’s history. In a time before railroads reached into the mountains and in a region without easily navigable rivers, thousands of hogs were driven through Asheville every year. This route, Essig says, led from the “mini corn belt” of East Tennessee along the French Broad River valley of North Carolina, allowing farmers in Tennessee and North Carolina to reach markets as far away as Charleston and Atlanta.

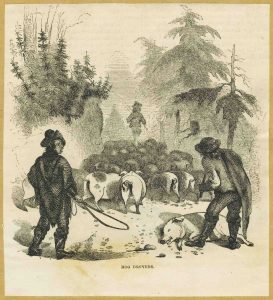

Each fall, the banks of the French Broad were crowded with hogs. In fact, they were marched directly through Asheville’s downtown along Broadway Street. Lame ones were sold or traded along the way and were periodically saved by the ear from drowning in the French Broad. “The accounts you would read are of tens of thousands of hogs being driven on the hoof through Asheville,” says Essig. These accounts list turkeys, mules, sheep, and cows as well, but mostly hogs, all heading south. They call up the noise of animals and their drovers, the pungent smells, and the feet of mud they worked up as they went.

Edmund Cody Burnett, a historian who wrote about hog farming in Buncombe County, remembered the turnpike from his childhood. He estimated that as many as 160,000 hogs in “vast herds” were driven through Asheville each fall. Since hogs can only be driven about ten miles a day, inns sprang up to house the young men who guided them. Young drivers who followed behind the hogs slept on pallets, and the experienced drovers who led the way fit three to a bed.

“In October, November, and December, there was an almost continuous string of hogs from Paint Rock to Asheville,” Burnett wrote. “I have known ten to twelve droves, containing from 300 to one to two thousand, stop overnight and feed at one of these stands or hotels.” He remembered them as a “surging parade,” with the air punctuated by the “ho-o-o-yuh!” calls of the drivers and the cracks of whips.

The route eventually became the Buncombe Turnpike, also known as the Drovers’ Road, authorized by the State of North Carolina in 1824. Improvements to the road opened the area to tourism and increased wealth, but animals and drovers continued to move in waves along the turnpike and its tributaries for more than 100 years, until 20th-century highway and train travel. Those hog statues in Pack Square are a commemoration of the herds that helped Asheville to become the city it is today.

History Guides the Future

Jamie Ager, co-owner of Hickory Nut Gap Farm, grew up steeped in this history, with the Old Sherrill Inn beside the Buncombe County farmhouse where he was raised. The inn was a stock stand, which offered rest and food not only for the drovers, but also for their livestock. The walls are made of hand-hewn paneling, and the patched wide-plank floors undulate. One can imagine weary travelers climbing up a large front porch that stretches the length of the building. Ager pushes on a bookshelf in the library to reveal a secret room where the innkeeper kept the cash. He flips through a copy of the ledger from the inn, where scrolling handwriting records one particular drover who stayed the night in 1882.

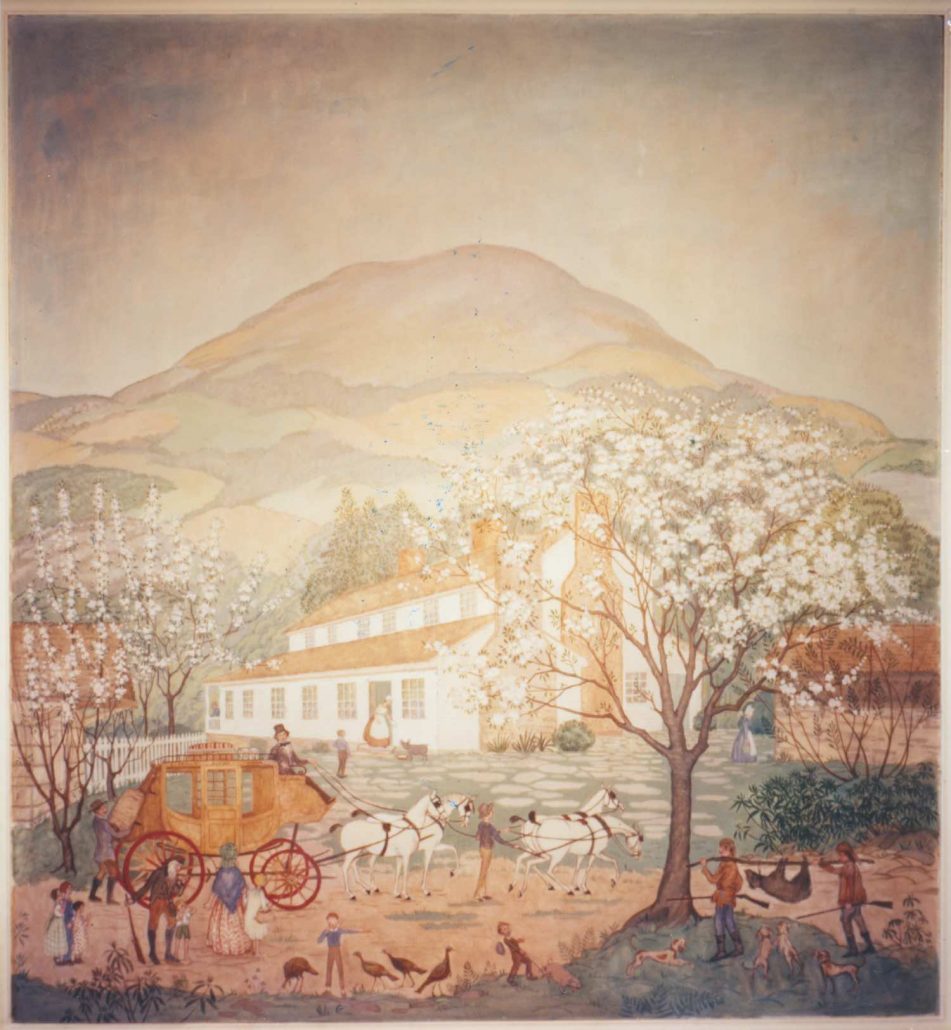

Titled “Old Days at Sherrills,” this mural is one panel in a series painted by Elizabeth Skinner Cramer McClure. Located near Hickory Nut Gap Farm, the inn offered rest and food for drovers and the livestock they oversaw. Photo courtsey of the North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

Ager’s family bought the Old Sherrill Inn in 1960, and his great-grandmother covered the walls of the inn with scenes from its history. Ager wrote his undergraduate thesis at Warren Wilson College on the subject, and he can point to the indentation in the yard of the Sherrill Inn where decades of hog travel wore a divot in the yard that still persists.

Ager started Hickory Nut Gap Farm on his family’s property shortly after he graduated in 2000, producing grass-fed, pasture-raised meats. By the mid-2000s, he was ready to grow the business by reaching out to other farmers in the region and supporting them to produce meats in this same manner. As he talks, he repeats the word “connection.” By this, he means connections between farmers, between consumers and producers, between the history and the future of livestock farming. It’s about understanding and knowledge, and, almost serendipitously, taste.

Mid-morning visitors to the farm might see Ager’s hogs being herded across the fields in a way that must be similar, if much shorter and less frantic, than the hog drives of the 1800s. Several men herd the animals from the back with piercing but friendly calls the animals seem to understand. They move as one, though they may stop to take a bite of grass or playfully roll over one of their fellows. Four are headed to slaughter, but they are moved as a group because they prefer to travel together, reducing their stress until the last possible moment.

The hogs are particularly good at clearing out land that the Agers want to use for pasture. “We stick them in the woods, in big patches of multiflora rose,” Ager says. “They do a great job of ripping that stuff out.”

Connecting Farmers and Consumers

Ager welcomes consumers to Hickory Nut Gap to see the pigs at play. Visitors purchase meats, pick blueberries, learn how the animals are raised. It’s all part of a very intentional business plan. Ager is betting that the more consumers know, the better choices they’ll make.

According to Molly Nicholie of ASAP, this kind of direct relationship between farmers and consumers have driven recent changes in the industry here. “Between 2007 and 2012, Western North Carolina saw a 70-percent increase in direct sales,” she says. “The rest of the state actually had a decrease in direct sales.”

Ager sees great benefits for the farmers and animals as well as for the consumers and chefs: In addition to the four or five hogs a week Hickory Nut Gap slaughters in Fairview, they work with other farms, some of which are in Eastern North Carolina, to slaughter an additional 60 per week. This is important to Ager, who sees the power in providing farmers more control over what they produce and how they sell it, and in providing consumers with the knowledge to make informed choices about what they eat.

“My big vision,” says Ager, is to “really drive agriculture into a partnership paradigm between farmers and consumers.” This connection would not have been strange to drovers 200 years ago selling lame pigs to innkeepers and eating that same bacon for their breakfasts, or subsistence farmers who knew where their animals would forage and how to draw them back home before slaughter. ◊◊

Beth Lassiter’s grandparents were subsistence hog farmers in Gates County, NC. She grew up in the land of all-night pig pickins, country ham biscuits, and dandoodles in collards. Her father spoke kindly of his pet pigs Dick and Jane, who later went to slaughter.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Asheville-based historian Mark Essig explored the relationship between hogs and humans in this popular 2015 book.

This engraving appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1857 and was titled “Hog Drovers,” showing drovers moving their hogs with whips.

Photo courtsey of the North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.