The Poinsett Bridge

by Mark Essig

The Poinsett Bridge looms in the forest like something medieval. You half expect to find a troll lurking under its gothic arch. The South Carolina bridge dates to 1820, which by the standards of Appalachian architecture counts as ancient. And though it now lies just off the little-travelled Callahan Mountain Road, “it wasn’t out of the way at the time it was built,” says Penelope Forrester, a member of the Greenville County Historic Preservation Commission.

Nearly two centuries ago the bridge carried traffic on the State Road, a main thoroughfare that ran from Charleston through Columbia and up to the state line at Saluda Gap. There it joined North Carolina’s Buncombe Turnpike, which ran through Asheville and up through French Broad River Valley to Tennessee.

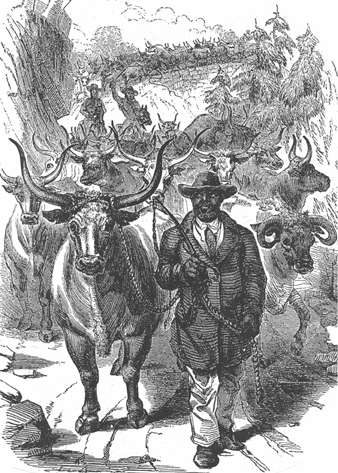

The bridge was built to last, because it had to withstand the pounding of wagon wheels and droves of horses, hogs, and cattle.

A state official in 1818 explained that the new road would “attract a great portion of the trade of East Tennessee to this state.” At the time, East Tennessee was a booming agricultural region whose farmers drove their hogs and cattle to market either north through Virginia or south through the mountains.

South Carolina built the State Road to encourage traffic to move in its direction. The state’s plantation economy was so single-mindedly devoted to growing cotton that it needed to import food.

When the road-building was completed, in the late 1820s, the spigot opened and a river of livestock began to flow. In 1847 one toll gate in South Carolina recorded 40,000 hogs, 4,500 cattle, and 3,500 horses passing along the State Road. Turkeys, as many 600 per flock, made the journey as well. And since the birds were notoriously reluctant to wade across streams, turkey drivers must have been especially grateful for the Poinsett Bridge.

Given the demands of the traffic, the state took particular care with the construction of Poinsett Bridge, which spans Little Gap Creek, and two other stone bridges nearby on the route. (The two others now lie in ruins under the surface of the North Saluda Reservoir.)

Robert Mills, the architect who later built the Washington Monument, may have designed the bridge, though the evidence for his role is not airtight. Abraham Blanding, a commissioner on the state’s Board of Public works, personally oversaw a crew of 500 workers, including enslaved African-Americans, white laborers from the mountains, and stonemasons brought in from Boston and Philadelphia.

The bridge came to be named not for the men who did the work but for Joel R. Poinsett, president of the Board of Public Works, who dispensed orders from afar. (“The big boss always gets the credit,” Forrester explains.) Poinsett, a politician and diplomat, later re- turned from a trip to Mexico with a red-leafed plant that, like the bridge, was named in his honor.

Though the State Road carried mostly livestock in the fall, a different type of traveler made the journey in the early summer. Planters from the Low Country, seeking to escape the heat, mosquitoes, and diseases of the Atlantic Coast, began summering in the mountains, marking the emergence of Western North Carolina as a tourist destination.

Now the bridge is a quiet tourist spot itself, the centerpiece of the 120-acre Poinsett Bridge Heritage Preserve. Just downstream from the bridge, a sloping shelf of stone in the middle of the creek provides a natural water slide for visitors with a sense of adventure and sturdy swim trunks. Those with quieter interests can stroll across the bridge and down a few thousand feet of the original road bed, following in the hoof prints of tens of thousands who went before.

Mark Essig is Edible Asheville’s managing editor and the author of Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig, which includes a short history of Appalachian livestock droving.

Historic cattle drove on the Poinsett Bridge. Bridge photos by Mark Essig.

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.