THE FLAVORS OF 50 MILES

The story of one local woman who sourced a complete diet from food grown or raised within 50 miles of Asheville

BY MARI JYVÄSJÄRVI STUART | PHOTOS BY ERIN ADAMS

Presented by Mother Earth Food

PLANTING THE SEED: THE FIRST CHAPTER IN A FOUR-PART SERIES

Local food” is on everyone’s lips—but perhaps it’s the phrase that’s more common than the actual food.

Of course, local food is hip. But apart from the occasional trip to the farmers market, how many people actually source the bulk of their diet from their region? Supermarket food, shipped from thousands of miles away, remains overwhelmingly the norm.

Last fall, I decided to confront the uncomfortable fact that I think of myself as a local food enthusiast, but most of the staples in my pantry—like rice, pasta, and flour—and even many things that could be available locally come from faraway places. What would it take to source all of my food from within my region? Could it really be that hard—and if not, why don’t more of us do it? So in September 2019, I committed to one month of eating nothing but food grown or raised within a 50-mile radius from my home.

Connecting to place through food is something I know from my childhood. I grew up in northern Finland, where there’s snow half of the year and the growing season has barely begun when it already ends. A “local diet” there is a hearty but bland diet that my ancestors survived on: root vegetables, game, fish, and bread. Even though modern Finns have eagerly embraced the variety and exciting flavors of imported grocery store foods, the ethos of eating from the land persists. Heading to the forest to forage wild berries and mushrooms is a national obsession. My father hunts game. In the summers, we would grow our own potatoes and currants and whatever else could be grown during the short arctic growing season.

When I left Finland as a college student, I threw myself full-force into a life of nomadic adventure. I studied, traveled, and volunteered on five continents. I lived in all four corners of the U.S. while pursuing first graduate study and then an academic career.

There wasn’t much time for exploring local food; I was never in one place long enough to be “a local” myself. It didn’t help that as a scholar, I was trained to live inside my own head, decoupled from my material life, and rewarded for it.

But nine years ago, a series of personal crises converged on the realization that I longed for a more grounded life. I felt an irresistible urge to put down roots and understand where the makings of my material life came from. I planted a garden, enrolled in a permaculture design course, and started learning to make just about everything from scratch. I read Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, the modern classic of the American local food movement, and savored every word. I, too, wanted to be able to trace the food on my plate to where it came from, to find alternatives to the industrial food system. But, I told myself, Kingsolver and her family had a small farm and were able to produce much of their own food, whereas I was an urban renter with a tiny container garden.

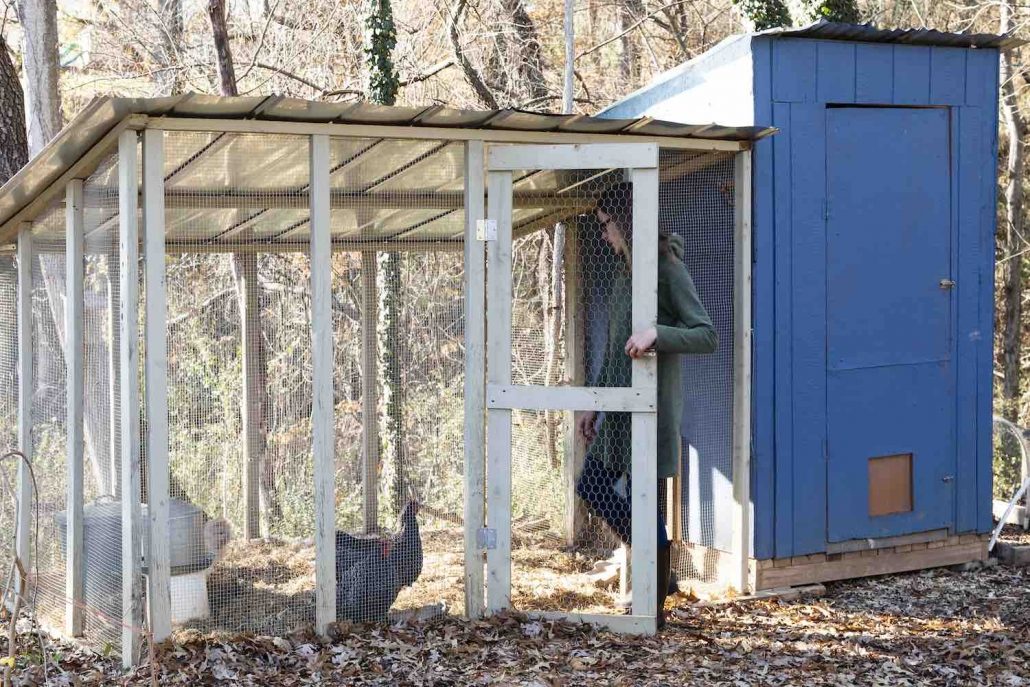

It took a few years and a few more moves, but finally my husband and I managed to settle down in our first home in Asheville and started developing it into an urban homestead. While still not a farmer, I now have a decade of gardening experience under my belt and a good-sized vegetable garden. Weekly visits to the farmers markets have made me familiar with the local food scene. Eating from the landscape I inhabit has finally started to seem possible.

I decided to start with a month of eating local food, as opposed to a whole year, to test the waters. I chose the month of September which was, in retrospect, almost like cheating. After all, September is the peak of the harvest season, and farmers market stalls are on the brink of collapsing under the weight of shiny peppers, bodacious tomatoes, widely smiling ears of corn, and greens, potatoes, and sweet potatoes piled high.

As the first day of my local eating experiment approached, my husband expressed some reservations—on two counts. First, he was worried that I would exhaust myself, as I tend to do with any new project, sourcing all-local foods and making everything from scratch. Second, he predicted that our grocery bill for that month would soar.

It’s true that I spent more time in the kitchen during my locavore month than I normally do. After all, there’s a reason why they call it “slow food.” When convenience foods are out, you make the stock from scratch, you roll out the tortillas and the pasta. But when we did the accounting at the end of the month, we found that we did not spend significantly more money on food that month.

As for our 5-year-old daughter—who is a picky eater, as it is—I decided I would not insist on her sticking to a 100-percent local diet. Our shared meals were cooked with local ingredients, but she got to have some of her comfort store-bought snacks.

◊◊

Why eat local? Why go through the trouble, when a mind-boggling variety of imported foods is easily and affordably available at the supermarket?

There are compelling reasons, and more and more people take them seriously, as the growing strength of the local food movement indicates. People choose local foods because of the fossil-fuel footprint of foods being shipped around the world and the detrimental effects that the industrial food system has on both ecosystem and human health. The very same system that provides most Americans with cheap, abundant food makes them simultaneously overfed and malnourished. There is little transparency about the sources of food, how it was grown and processed, and what chemicals, pesticides, or additives it contains.

In contrast, when you eat local, you know exactly what you’re putting into your body. You can talk to the farmers themselves about their growing practices. A local diet is essentially a whole-foods diet that nutritionists and doctors tell us is better for us anyway. Local fruits and vegetables are also fresher than imported ones, which matters because the nutrient value of produce starts to drop as soon as it is harvested. By the time a head of organic California broccoli gets to you, some of its cancer-fighting properties have already dissipated.

Lastly, sourcing our food locally supports the regional economy, especially small farmers. At the end of my locavore month, when I looked at where I had spent money on food, it was all local farms, farmers markets, dairies, and our local food co-op. None of our family’s food dollars that month went to the big supermarket chains; they stayed local.

Taken together, all of these reasons motivate my choice to try to eat locally. But there is something else besides. I want to connect with the source of my food. I want to experience that interdependence with one’s regional landscape that our ancestors took for granted. I’m also after some real pleasures: fresh, distinct flavors and aromas—the terroir of our beautiful mountain region, the delight of seasonal food that tastes heavenly precisely because it’s only available for a limited period of time. There is simply no strawberry imported in January that can ever compare to the persimmons, figs, pawpaws, apples, and Muscadine grapes I foraged and devoured in a single afternoon, my hands sticky with their warm juice.

Local eating is activism that tastes delicious. Local food makes people feel connected, and connection is, after all, one of the things we’re hardwired for.

◊◊

If you are contemplating a more locally sourced diet in the Asheville area, here’s the good news: compared to many parts of the country, the Asheville area is a phenomenally easy place to explore local eating. Seasonal vegetables are avail- able year-round. There’s a local dairy and several artisanal cheesemakers, and those of us who consume animal proteins can find a range of eggs and meats from quality producers. Two local grain mills are committed to working with regional growers of wheat and corn. There’s a sustainable local fish farm. We even have some farmers growing rice.

On the other hand, some of the staples of the standard American diet are not as easy to find. Western North Carolina is not exactly the breadbasket of the country. Hard red winter wheat does not do well in our humid climate and relatively warm winters. Other key staples for our family that I found hard to find were oats and lentils. Finally, there’s the question of oils. Even the most committed local food advocates still tend to cook with imported oils.

But you know you live in a local food hot spot when you can find ways around these challenges, solely thanks to the enthusiastic and innovative people working with our region’s food systems. In the second part of this series, coming in the Spring Issue, I will share some of the lesser-known resources and local ingredients that you, too, can bring to your table. ◊◊

Mari Jyväsjärvi Stuart is an ecological landscape designer, teacher, and regenerative agriculture advocate. She is the program director for Co-operate WNC’s new community-supported regenerative farming initiative. She is also on the core faculty for SIT Graduate Institute’s M.A. in Sustainable Development, and she teaches modern homesteading skills in her community.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Mari Jyväsjärvi Stuart with her 5 year old daughter and husband.

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.