SAVORING THE PAST

Restaurants’ historic preservation efforts help craft the character of Asheville

BY GINA SMITH

***

One of the key components of Asheville’s distinctive charm is its antique architectural gems. From towering downtown structures to single-story storefronts throughout the city, buildings designed in the Gothic, Art Deco, Neoclassical, and Romanesque Revival styles are a hallmark of the city’s beauty.

The presence of these old buildings, however, is more a byproduct of financial stress than an intentional effort by city planners to preserve the past. An enormous debt burden incurred by the city during the Great Depression prevented it from demolishing any old buildings in favor of newer designs—a reality that, at the time, felt like the city was stuck with what it had.

Nowadays, nearly a century later, competition is high for Asheville retail properties, and business owners—including numerous restaurateurs—are undertaking the restoration and preservation of these exquisite historic structures, adapting antiquated spaces to propel the city into a bright culinary future while grounding it firmly in the legacies of its past.

Embracing and encouraging many of these efforts is the Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County. Formed in 1976—the year Asheville finally paid off its Depression-era debt—the group honors local renovation and preservation work with Griffin Awards. According to PSABC Director of Preservation Erica LeClaire, more than 400 Griffin Awards have been given out over the years, and many of the winning projects have been restaurants.

The interior of the building that now houses Buxton Hall Barbecue before renovation.

Adapt and Reuse

Restaurant restoration projects in Asheville run the gamut, says LeClaire. Some are makeovers of functioning spaces, like Chai Pani’s extensive 2018 glow-up, which won a Griffin Award for rehabilitation. Others entail a wholesale buildout of condemned or otherwise unusable structures, like the 2022 Griffin Award-winning Harvest Pizzeria project on the South Slope that started with just three walls and some steel roof trusses from an old auto repair shop.

”Basically, they just take an old building that was meant for something else and put it back into use, which we love to see,” LeClaire says. “The building is saved, and it’s given a new life.”

In addition to preserving historic architecture, adaptive reuse promotes environmental conservation, LeClaire points out. “The building materials will stay in use, the embodied carbon will stay there, and we’re not using more non-renewable resources to build something new or to demolish something; we’re not bringing more materials to the landfill. We’re putting all that back into use in a new way, which is a really cool way to kind of hit on several values that this community cares about.”

In Burial Beer’s 2020 Griffin Award-winning Forestry Camp project, for example, all of the wood used in restoring the six historic Civilian Conservation Corps camp buildings from the 1930s was sourced from the site, which both conserved resources and maintained the structures’ original rustic aesthetic.

“This project touched an entire campus of buildings that were in rough shape,” she says. “Each of the buildings were thoughtfully rehabbed to be put back into use for their production, administration, and hospitality needs.”

Although there are many challenges inherent to re-envisioning old spaces, especially when they’re in poor condition, LeClaire says, the rewards outweigh the drawbacks. “When you can look past some of the things that might be a little more negative, you can come up with a really cool project to save some beautiful architecture around town.”

The building that now houses Chai Pani before its renovation.

Labor of Love

When Sean and Shelly Piper purchased the small, condemned building at 715 Haywood Road in 2014 with plans to open a restaurant, they were drawn to the property’s affordability and desirable location. With competition fierce for real estate, the Pipers decided they were willing to deal with the building’s drawbacks. As a former shoe store that had been abandoned for many years, the space had at some point experienced a fire, the roof was rotted, the floor had holes in it, and vagrants had been living inside.

“It was in really bad shape,” Sean recalls. “It was so badly damaged that the rain runoff from that property was damaging the neighboring buildings.”

Piper admits that the prospect of renovating such a dilapidated structure and turning it into a restaurant was intimidating. It would have been far easier, he says, to demolish the whole thing and start from scratch. But once he discovered that the little building—once part of a busy West Asheville commercial corridor linked by an electric streetcar line in the early 1900s— was on the National Register of Historic Places, he was committed to preserving it. “I knew I could do it,” he says. “There were a lot of sleepless nights, though, when I was like, ‘Oh, my god, am I going to be able to do this?’ Because getting the building was one thing, but finding funds for the renovation was a whole other ballpark.”

Hundreds of thousands of dollars went into the project, Piper estimates, including his life’s savings and a contribution from his father. He worked with a specialist from the NC State Historic Preservation Office to follow the rules for conserving the existing walls, facade, and windows. “Luckily, there weren’t any intricate pieces like flying buttresses or spiral staircases to preserve like in some of these beautiful [historic] homes,” he says. “It can just blow up your budget when you’re trying to preserve these things.”

While continuing to work at his former job in the movie industry, Piper collaborated with two Asheville-based companies, Wilson Architects and Altitude Builders, to transform the tiny, run-down property into a functioning restaurant. One major task was digging a basement 10 feet below the floor to create extra room for a prep kitchen and storage area.

“We were fighting for every inch of space,” he recalls. “It was important to have a downstairs employee bathroom, so we needed to have a gravity system [for the water] because having a pump would be very, very expensive. We had to rip up the whole back alleyway to make those MSD connections, which was an insane task. I repaved it and pitched all the water away from the [neighboring] businesses, because during severe downpours, the water would run down into the basements of these old historical buildings.”

When it came time to develop the restaurant’s aesthetic, the Pipers tapped Shelly’s background in art history and museum administration to inform their upcycled, mid-century modern design vision. Using flooring Sean salvaged from a 1952 bowling alley in Indiana, local woodworking studio Golden Splinter crafted custom tables and the bar that now anchors the dining room. A wall of decorative mirrors, an antique record player and radio, framed vintage artwork, and tile mosaic in the vestibule all contribute to the atmosphere.

Open since 2017, the cozy, eclectic elegance of Jargon’s dining room belies the fact that it was once a decrepit, condemned building. “I’m so proud,” says Sean Piper. “There are little things now that I look at and think, ‘Oh, I wish I did that or could have done that.’ But overall, it’s a really great space for a restaurant.”

And winning the Griffin Award was an unexpected delight. “That was such an honor,” he says. “It was one of the last things I got to do with my father before he died, which just made him so proud. He got to join us for that ceremony, and it was a special moment for us as a family.”

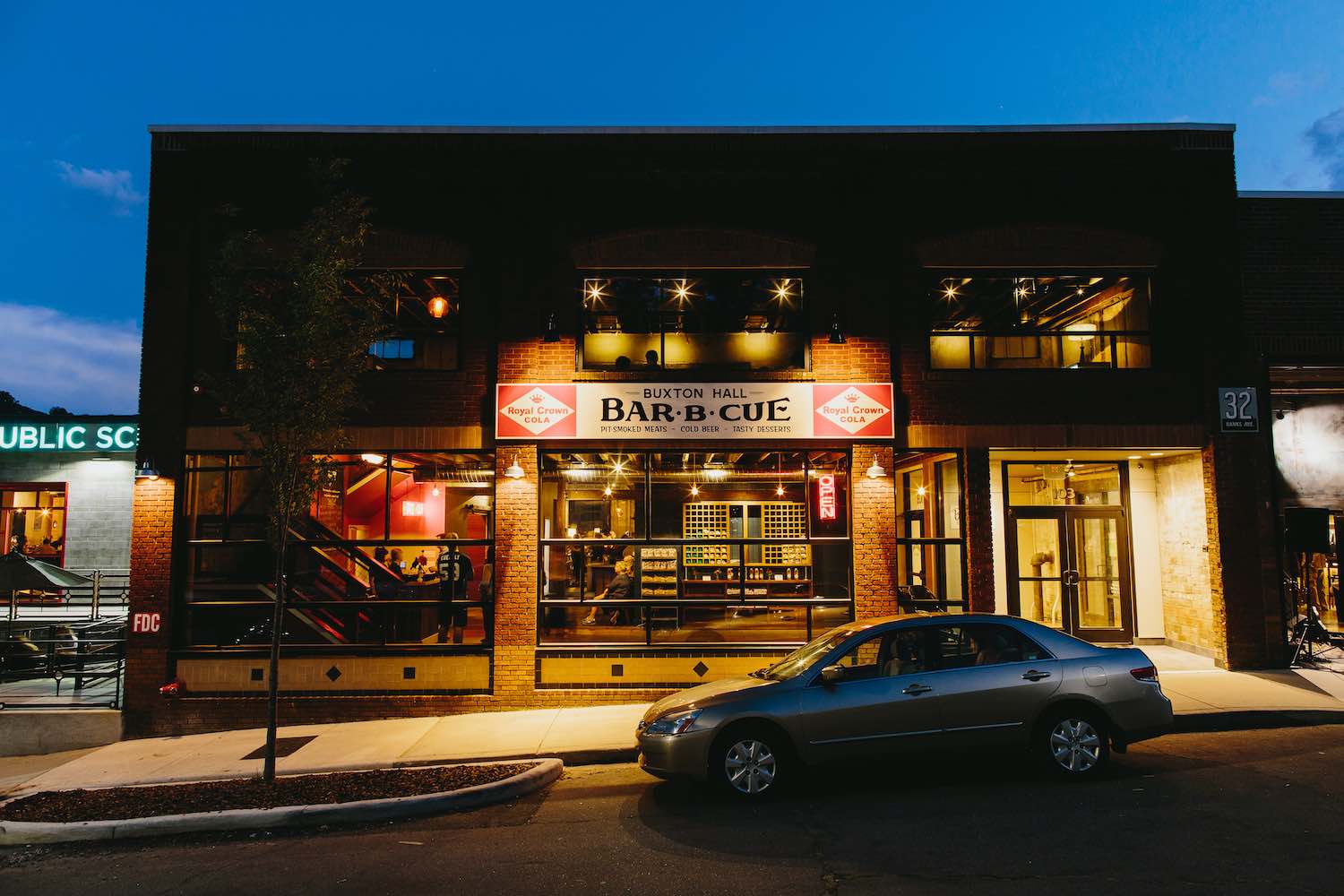

Buxton Hall Barbecue before and after renovation.

Peeling Back the Layers

Asheville restaurateur Meherwan Irani admits he has a thing for old buildings. One of the visionaries behind downtown’s S&W Market food hall and founder of the 2022 James Beard Award-winning Chai Pani, Buxton Hall Barbecue, and Spicewalla spice company, in addition to other projects, Irani has won three Griffin Awards—two for adaptive reuse for Buxton Hall and the S&W and a rehabilitation award for Chai Pani’s 2018 renovation. Restoring and repurposing historic buildings, he says, is a key part of his formula for creating successful restaurants with distinctive character.

“It’s a big part of deciding where any of my restaurants go—so much of it is driven by the space and the storytelling of the space or how the space is a perfect fit for the concept,” Irani explains. “The minute you make the place part of the story, paying attention to the way the building used to be is as important during the buildout as setting up your kitchen or your front of house or even your menu.”

While Irani acknowledges that there are plenty of challenges inherent to refurbishing, preserving, and retrofitting old buildings to fit the needs of a modern restaurant operation, he sees them as opportunities to be embraced rather than obstacles to contend with. He points to the work on the Buxton Hall building at 32 Banks Ave. on the South Slope as a prime example. As the former home of a wood-floored roller-skating rink in the 1930s, the space’s interior walls still bear the ghosts of athletics-themed murals painted around the time of the 1936 Olympics.

“We intentionally put the kitchen on the other side because we wanted to preserve the murals. Was that the best location for the kitchen to be? Maybe not. But we didn’t look at it from an engineering standpoint,” Irani says. “We just looked at it from, like, well, there’s no way we can ever cover up these murals, so it’s got to be on the other side.”

The placement of the bathrooms at Buxton—with an open area between them rather than in a more efficient side-by-side design—also resulted from efforts to preserve the murals. “One could have said that was a challenge and cost more money, but I look at it like it’s cool because it preserved that feature,” he says.

The historic features and background of the Buxton Hall building and the story of its preservation are intrinsic to the restaurant’s concept and make the dining experience more meaningful for guests, Irani says. “I’m trying really hard to imagine Buxton in a different setting in a different building, and I’m struggling to. I can’t even imagine what it would look like as an end-cap unit in a brand-new development. It wouldn’t be Buxton.”

With the Buxton Hall and S&W Market projects, Irani learned that much of the restoration process was about removing layers of materials added over the years to uncover the original nature of the building. Even with Chai Pani’s remodeling project, he says, it was more about stripping things away than adding new features.

When he and his wife, Molly, opened Chai Pani in 2009, they weren’t able to do much renovation of the space, and so they worked with what they had. But when they began their rehab project in 2018, they discovered that newer interior walls were covering the original brick and plaster shell. Removing those retrofitted walls not only opened up much-needed space in the footprint but also revealed some exciting features.

“When we took the wall out from the right side where the bar is, all this brickwork got exposed,” says Irani. “And when we took the wall away from the left side, we discovered there were these old plaster walls that had a lot of texture and character. And when we got rid of the ceiling tiles, we exposed what I believe is a much cooler-looking ceiling, which is the actual concrete and formed I-beams.”

Irani credits his partners with helping bring his visions to life. S&W partners Douglas Ellington and Burns and Anne Aldridge of Ellington Realty Group were onboard with the approach of returning the S&W to how it was originally designed—by Ellington’s great-uncle, architect Douglas Ellington—as a grand, Art Deco cafeteria in the 1920s. And contractors J&N Homes worked with architect Diana Bellgowan on the Buxton Hall renovation and several projects since, including S&W Market.

“In Diana, I found someone as obsessed as I am with what stories the space and building are trying to tell us and how do we make that shine through,” says Irani. “Diana went and found old images of the S&W, and we were able to look through those and see that, oh, that didn’t used to be there, and the ceiling didn’t look this way, and this was the actual color scheme for the interior. It’s a fun process, and it’s not as expensive as people often think it is, because often you’re just taking layers away.”

Noting a few other restaurant preservation projects around town that have interested him, including La Bodega by Curaté and Vivian, Irani is struck by how much these efforts mean to the Asheville community as a whole. “It means so much to so many people when you do it the right way—so much so that you can get an award for the work you do,” he reflects.

To any aspiring restaurateurs out there, he adds, “You don’t have to sign up for a brand-new, shiny building at the edge of town. There are plenty of opportunities in town. Just take a look at something from a whole new perspective, and just go, ‘What if?’” A life-long lover of food and gardening, tailgate market junkie, and former food-service worker,

Gina Smith has been a professional writer and editor for nearly two decades, hewing her writing focus nearly exclusively to food, beverage, and agriculture since 2013. In addition to her writing pursuits, she is the part-time coordinator for the Asheville Buncombe Food Policy Council.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Murals on the wall of Buxton Hall Barbecue before its renovation.

Murals on the wall of Buxton Hall Barbecue before its renovation.

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.