PERFECTION IN IMPERFECTION

Akira Satake savors Japanese style in life and art

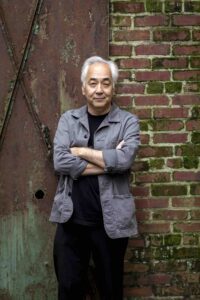

BY ALLI MARSHALL | PHOTOS BY ERIN ADAMS

Japanese-born potter and musician Akira Satake creates and displays work at his Gallery Mugen in Asheville’s River Arts District. His pieces range from home decor and sculpture to tableware, sake cups, and tea sets. Satake moved to the U.S. four decades ago. At the time, it wasn’t a total culture shock: He’d discovered folk musician Doc Watson at the age of 8, his formative years were spent listening to American bluegrass and blues, and he learned to play the banjo. “I grew up looking outside of Japan,” Satake says.

But it was his love of Japanese culture and food that eventually led the artist—whose previous career incarnation was as a professional musician, producer, and owner of the world music label Alula Records—to pottery.

Edible Asheville: For you, what is the connection between flavors from home and your ceramics practice?

Akira Satake: One of the greatest things about moving out of my own country was I could see more objectively what it was and what I missed. What I missed most was the food.

I’d always liked cooking and eating. In middle school and high school I was baking cookies. I’d go to the expensive grocery stores to try foods I’d never had before, such as avocado, asparagus, and lasagna.

But, with the move to this country, I started to cook what my mother was making—very traditional Japanese food. The passion for Japanese food became a really big part of my life and was one of the biggest reasons I became interested in making pottery.

EA: How does the Japanese influence show up in your home cooking and dining?

AS: I use all my pots (laughs). I cook pretty much every breakfast and every dinner. … My wife is a pastry chef, but in our house, I’m the main chef for savory, and she’s the main chef for sweets. I’m not a [professional chef] so I’m not looking for perfection. But at the same time, the visual is important for taste. The Japanese aesthetic of food decoration is quite different from all other parts of the world. It influenced nouvelle cuisine in France, big time.

Japanese food—it doesn’t have to be in a restaurant—uses many plates and dishes. My wife, who is American, complained to me many times, “Akira, you use so many dishes.” In Europe and America, it’s often one plate. We [Japanese] use three or four or five for each person. There are soup bowls, of course, and two or three small plates, then large bowls and serving bowls. Each dinner fills up the dishwasher.

EA: Are your customers looking for an array of dishes, or to use more plates in their presentation?

AS: It’s all kinds of people. To buy from me means they’re looking for Japanese style in decorating or using pots. But sometimes—including for myself—one plate is great. Less to wash (laughs). And it depends on the food. Sometimes mixing everything on one plate is good, but other times the subtlety of the flavor is destroyed when you put everything on one plate. Here, I make many small things and large things, some large plates. Good for any occasion and any kind of people.

Myself, I sometimes prefer one plate and sometimes prefer many small plates. In kaiseki [a traditional multi-course Japanese meal], you use about 20 plates. That’s fun, too.

The other thing is our life in Japan is really affected by seasons. It’s nice to use different plates and bowls for different seasons.

EA: Beyond ceremonial pieces, such as tea bowls, do you find thereʼs an inherent connection between ceramics and eating?

AS: Most people I know who are potters are interested in food. Not everybody is a good cook, but they care. At the workshops I teach, potlucks are an important part of the experience. When I had a workshop in France, that was one of the best things: the potluck. People were obsessed with and understood good food. I think any good potter is careful in how to [present] food on the plate. Space is probably one of the most important things for any art. Food—how to arrange it on your plate—shows artistry.

EA: How did you transition from being a musician to a potter?

AS: In the beginning of my musical life, I was playing for the love of performing and creating. As I began to make money, became a producer, and had my own company—in New York City, which was one of the craziest places to work—I got really, really stressed. I couldn’t sleep. I realized if I kept going like that, I’d kill myself. I had to do something. So I started doing pottery.

Once I [turned to] pottery, it was great. I was escaping from my other life. … I realized New York City was not the place for me. I didn’t know if I could make it full time as a potter, so for the first years I was back and forth [between ceramics and music].

EA: Were you surprised by the kismet of ending up in Asheville, so close to the home of your childhood hero Doc Watson?

AS: Definitely! How lucky I am.

My wife and I were talking about moving out of Brooklyn, wondering where we could go. … My friend said, “How about Asheville?” He’s a potter, too. So he knew of Penland [School of Craft], but he wasn’t really familiar with Asheville. [But] I’d heard something good about it, so I went home and checked on the internet, and everything I read about Asheville was great.

Probably I was trying to block the music part of my life, somehow. I didn’t even consider the musical heritage of Appalachia. But once I moved here and started to play a little music, they accepted me so much. I was invited to play the LEAF Festival. People were [aware of] my recordings. … The Asheville audience is so kind.

EA: How has COVID-19 affected your business?

AS: I was prepared for whatever change could happen. Luckily, I had an email list and quite a big following on Instagram and Facebook. In early March, when things started [to shut down], I immediately focused online, and that really saved [the business] and actually went beyond.

The most important thing for me is to continue challenging myself to make something new and something I want to create. I don’t want to get too busy [with online orders]. That’s not the point of being an artist. But it’s also good to reach more people, and it’s very flattering to be recognized by more people. I’m starting to reach a lot of people from Europe and Asia, and that’s a wonderful feeling.

I love to teach. This year I was supposed to do two-week workshops in Tuscany, Northern Italy, and Barcelona. All of those were cancelled because of the pandemic. So, instead of that, I did a virtual workshop. I limited it to 30 students, and many of those students were from outside of the U.S., so I thought, “This is great! I can reach people who wouldn’t have been able to come to my workshops.” ◊◊

Alli Marshall is a poet, performer, writer, editor, film maker and creative community builder. She’s interested in moving writing beyond the page, seeking the golden in the mundane, finding the intersection of art and social justice, and reconnecting with mythology—both ancient and modern. She makes a mean green smoothie. Find Alli at linktr.ee/amfmbroadcast

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Akira Satake of Gallery Mugen

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.