MAKING SENSE OF MOUNTAIN FOOD

A Q&A With Erica Abrams Locklear

WRITTEN BY BROOK BOLEN | PHOTOS BY NATE BURROWS

***

Erica Abrams Locklear is a professor of English and a Thomas Howerton Distinguished Professor of Humanities at UNC Asheville. A native of Western North Carolina, her research interests include Appalachia, foodways, gender and the South.

Abrams Locklear’s most recent book, Appalachia on the Table: Representing Mountain Food and People, looks at how stereotypes surrounding the food of Southern Appalachia are also used to support stereotypes about the people who live here. The book, released earlier this year, was listed as a top summer reading pick by Garden & Gun magazine, which described Abrams Locklear as “one of the preeminent voices in Appalachian literature, history, and culture.”

*

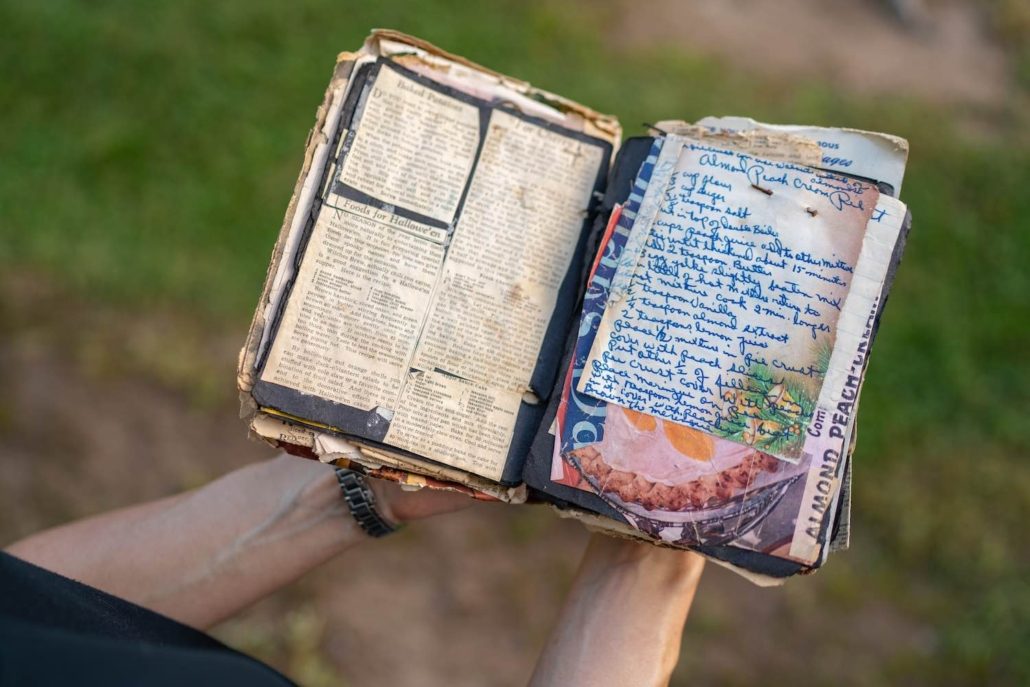

Edible Asheville: Your most recent book, Appalachia on the Table: Representing Mountain Food and People, was inspired in part by an old cookbook you discovered that had been compiled by your maternal grandmother. Can you tell us how that cookbook in- fluenced the book?

Erica Abrams Locklear: I had been working on the book project for a while when my mother found the cookbook in my grandmother’s house. That summer I was reading late 19th- and early 20th-century depictions of food in Appalachia and realizing that popular fiction and travel narratives set up corollaries between “coarse” food and “coarse” people. I was thinking a lot about how those derogatory, offensive descriptions shaped national perceptions of mountain people.

When I read my grandmother’s cookbook, which she made from 1936 to 1952, I was astounded to find the perfect counter-narrative. It follows genre conventions, with sections for recipes, household hints and home remedies. It also contains handwritten recipes, as well as recipes from magazines, newspapers and product boxes, all of which debunks ugly stereotypes about illiteracy in the mountains.

Perhaps most importantly, the diversity of recipes she included surprised even me. I was shocked to see recipes that called for specialized equipment, imported ingredients and time-intensive steps. It was a wakeup call that, despite my immersion in Appalachian studies, I too had been shaped by those century-old narratives, and here my grandmother was setting the story straight.

Yes, there are recipes for apple dumplings, chow chow and biscuits, but there are also recipes for fig pickles and devil’s food cake with coconut icing.

What do you make of the evolution of the representation of Appalachian foods from backward and low-brow to being trendy and widely celebrated? How do you explain it?

It really is a noteworthy shift. The same month my book was released, Bon Appétit magazine included a 16-page spread called “Appalachia Anew” that includes recipes and stories about mountain food. Meanwhile, food lovers flock to restaurants like Sean Brock’s Audrey, in Nashville, and John Fleer’s Rhubarb, here in Asheville, both of which celebrate Appalachian cuisine.

As to your question, chefs like Brock, Fleer and Travis Milton have had a lot to do with it, as well as talented cookbook authors and food writers like Ronni Lundy and Sheri Castle.

Hallmarks of Appalachian food are preservation, whether through drying (think apples or green beans) or pickling (think chow chow, sauerkraut and pickles) or foraging (think ramps, creasy greens, poke sallet and more). Over the last 20 years or so, chefs and food writers have highlighted how these food traditions are evidence of creative, resourceful people who know how to put a delicious meal on the table.

Even so, it’s clear to me that while Appalachian food has been venerated, national perceptions of mountain people have not. We still have a lot of work left to do on that front.

*

Garden & Gun named your book one of the Best New Books for Southerners in 2023, and you’ve been doing readings across the Southeast since its release. What has that experience been like?

It’s been great! It has been such a pleasure to be in conversation with chefs like John Fleer, food writers like Ronni Lundy and Sheri Castle, and those who lift up mountain literature, like Kendra Winchester of Read Appalachia.

I’ve done bookstore events, as well as public lectures, library visits and book club talks. These discussions also remind me that long-established stereotypes about mountain people are still in circulation. One person told me she was “so surprised” that my grandmother had taken college-level classes. Another insisted that in the 1920s, Buncombe County residents would’ve needed instruction in proper bathing. Although hygiene classes were part of Progressive Era initiatives, this woman seemed certain the majority of residents in rural Western North Carolina would’ve needed such instruction.

These deeply hurtful misunderstandings have only come up a few times, but they let me know that this book is important in educating readers.

*

What inspired your interest in the topics covered in your book?

I grew up in Leicester, and both sides of my family have been in Western North Carolina for generations. As a child I felt deeply rooted here, and that connection persisted when I left home to pursue various degrees.

When living in Utah I was reading [Southern fiction writer] Lee Smith’s work and thinking about home; in Louisiana I took a folklore seminar and interviewed my father and his friend about the cultural significance of ramps; it became my first published essay.

I realized early on that Appalachia could and should be the focus of my research, but it took me longer to realize that foodways could be a primary focus too. When I began reading work by culinary historians and scholars who considered the politics of race, class and gender through food, I was hooked.

For folks interested in learning more about Appalachian foods and foodways, which contemporary voices and works should they check out?

Ronni Lundy is unquestionably the leading expert on mountain food. Her cookbook, Victuals, is required reading. While it isn’t as recent, Sidney Saylor Farr’s More Than Moonshine is a valuable cookbook that’s also part memoir. Farr’s follow-up, Table Talk: Appalachian Meals and Memories, is also fantastic.

If you’re looking for food in recent literature, check out Crystal Wilkinson’s work; she has a food memoir coming out in 2024 that I’m very excited about. North Carolina poet Michael McFee often includes food imagery in his poems, and Robert Gipe’s commentary on the current craze over mountain food in Pop is pure brilliance.

If you’re considering southern food more broadly, two of my favorites are Elizabeth Engelhardt’s A Mess of Greens: Southern Gender and Southern Food and Marcie Cohen Ferris’s The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region.

*

Any other authors or works you consider to be fundamental to the topic of Appalachian cuisine?

One of the best things about the study of food is that it’s interdisciplinary: You’re considering work by food writers, cookbook authors, his- torians, culinary historians, literary critics, fiction writers and so much more. I also include chefs in this list because menus are texts that deserve analysis, too. So in no particular order: Ronni Lundy, Sheri Castle, Elizabeth Sims, Lora Smith, Elizabeth Engelhardt, Crystal Wilkinson, Robert Gipe, Sean Brock, John Fleer, Travis Milton and perhaps most of all, the countless women who have written down their recipes for homemade cookbooks, recipe files and community cookbooks.

*

As the glorious fall season unfolds, are there any foods you especially love to enjoy as the temperatures drop in the mountains?

It’s hard to beat a piping hot bowl of soup beans with cornbread. When the weather turns cold, I also start thinking about leather britches. I did not grow up eating these dried green beans that are rehydrated and then cooked, but a few years ago my dad spent hours threading beans and gave me leather britches for Christmas. Since then, I cherish each pot that I cook and enjoy, knowing how many hours went into that bowl of beans that taste like a father’s love.

*

Are there any dishes from your grandmother’s book that you love? If so, can you tell us about a few of your favorites?

Maybe this is clichéd, but I really like chow chow. I like the flexibility of adding whatever summer vegetables you have on hand, and I like the secrecy surrounding which spices to add and how much of each one.

It’s also a condiment that goes with everything: soup beans, tuna salad or any other protein you’re looking to make tastier. Also, I haven’t yet, but I want to make the fig pickles!

*

What’s next for the future of Appalachian food, foodways and Southerners?

This is an exciting time for Appalachian food. It’s finally being celebrated, and there’s a grow- ing recognition that Appalachian cuisine includes a diverse array of foods and culinary traditions. The feature in Bon Appétit I mentioned earlier makes that clear. Celebrating mountain food and at the same time highlighting the diversity in these mountains is a delicious future to consider.

Born and bred in Western North Carolina, Brook has written for a variety of local and national publications, including WNC magazine, Salon and Reader’s Digest. When she’s not writing, cooking or eating, you can find her in her garden or snuggling her kid and three rescue dogs.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.