EATERIES OF A BYGONE ERA IN A POPULAR FOOD TOWN

BY NAN K. CHASE

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE NORTH CAROLINA COLLECTION, PACK MEMORIAL PUBLIC LIBRARY IN ASHEVILLE

The clank of dishes and chatter of happy diners are nothing new in Asheville. Years before the city achieved national recognition for its vibrant culinary scene, back when tourists first started to arrive in the early 1800s, chefs and entrepreneurs opened bustling restaurants in our mountains—and then, eventually and sometimes without fanfare, closed them. Most folks today wouldn’t even recognize the restaurants from this bygone era.

Several months ago, I became interested in learning more about these forgotten eateries in what is now one of the most celebrated food towns in America. In December, I published a new book, Lost Restaurants of Asheville with Arcadia Publishing. I profiled 32 dining establishments that were popular in the 20th century, but almost all of which have since closed. I found everything from fancy white-linen restaurants to raucous roadhouses, from smoky neighborhood diners to tourist-friendly cafes. And then, of course, there were those early popular drive-ins.

Some, like Swiss Kitchen and Hillbilly Rest-Runt, have vanished without a trace, while others, like the F.W. Woolworth Co. lunch counter and the S&W Cafeteria, are instantly recognizable by their distinctive architecture.

The time frame of the book stretches from the Gross Restaurant, founded sometime in the 1890s, to Burgermeister’s, which closed in 2013. In between came such well-loved—or at least notorious— institutions as Hot Shot Café, Ritz Restaurant, Three Brothers Restaurant, Chez Paul, High Tea Café, Stockyard Café, and Laurey’s Gourmet Comfort Food.

The story of Asheville’s lost restaurants is also a social history of the city: the contributions of its immigrants, the crushing impacts of racial segregation, the boosterism and enthusiasm for community spirit, and the effects of national economic trends on family-owned businesses. In other words, all of these places are a window into the time in which they operated.

Of all of the restaurants I researched for the book, three of them stand out to me—in part because they were relatively well known and will be recognizable by modern-day readers, but also because they tell important stories about Asheville and what it is today.

S&W Cafeteria: An Art Deco Dining Destination

How could a restaurant operate for decades as a thriving focal point of a community—and then lapse into a memory and become known mostly for its architectural glory?

That’s the essential question about downtown Asheville’s most well-known commercial building: the 1929 architectural masterpiece built as the S&W Cafeteria.

Only in Asheville and only at the apex of its 1920s expansionist glory could a building like the S&W Cafeteria become a reality. The building still stands today at 56 Patton Avenue, and not much has changed except for one crucial difference. For more than 50 years, the S&W was a community gathering place where thousands of people would eat on a typical day. In recent years, the building has sat empty and struggled to find successful tenants.

In the 1940s, the S&W typically served 3,500 meals a day—breakfast, lunch, and dinner—and up to 5,000 in the busy tourist season. It seemed every civic group in town held meetings there, from the United Textile Workers of America to the Buncombe County Republican Club to the Latin Club of Lee H. Edwards High School.

Once that function was lost, on a day in 1974 when the restaurant moved to the Asheville Mall, the good times were mostly over.

Since then, the S&W Cafeteria building has beckoned to numberless entrepreneurs, but subsequent tenants have gone belly up. The building itself is partly to blame, for its creator, the architect Douglas D. Ellington, visualized it as one decorative, functional whole. The interior was as richly decorated as the exterior. There was a large main room with space for three buffet lines, a mezzanine, side rooms, private rooms upstairs, a basement, and an elaborate double stairway. While impressive, it no longer suits the needs of many modern-day operations.

Life may return soon to the S&W building. Last year, Highland Brewing Co. announced that it was joining forces with local chef Meherwan Irani, owner of the popular Chai Pani restaurant, to create a taproom and curated food hall concept in the building. It is slated to be called S&W Market.

Rabbit’s: Beacon of Pride

Imagine Asheville in the 1940s, with racial segregation creating two cities: one white, one black. A motel for African American guests, known as Rabbit’s Tourist Court and located at 110 McDowell Street, included the famous “soul-food stronghold” known simply as Rabbit’s. In the era of Jim Crow laws, when black tourists routinely encountered harassment at hotels, restaurants, gas stations, and rest stops, Rabbit’s was an establishment where they could comfortably dine and stay the night.

“You couldn’t eat in a white-run restaurant,” says Louella Byrd, a relative of Rabbit’s founder. “There was nowhere for black people to go.”

Rabbit’s was one of the establishments featured in The Negro Motorist Green Book, a national directory for African American tourists and travelers who wanted to locate businesses they could frequent without rejection.

Once at Rabbit’s, the menu was a crowd-pleaser. It featured macaroni and cheese described by one restaurant reviewer as “smothered under a carpet of cheese” and cornbread served hot from the oven, “cracking open and running with butter, a meal in itself sponged with a glass of buttermilk.” The pork chops, meanwhile, were “as thick as Bibles.”

In Rabbit’s later years, the diner offered lunch service, in addition to dinner, and hired a new chef to modernize its menu by lightening calories and adding baked items to fried fare. Still, the restaurant closed in the early aughts, and the building is now boarded up.

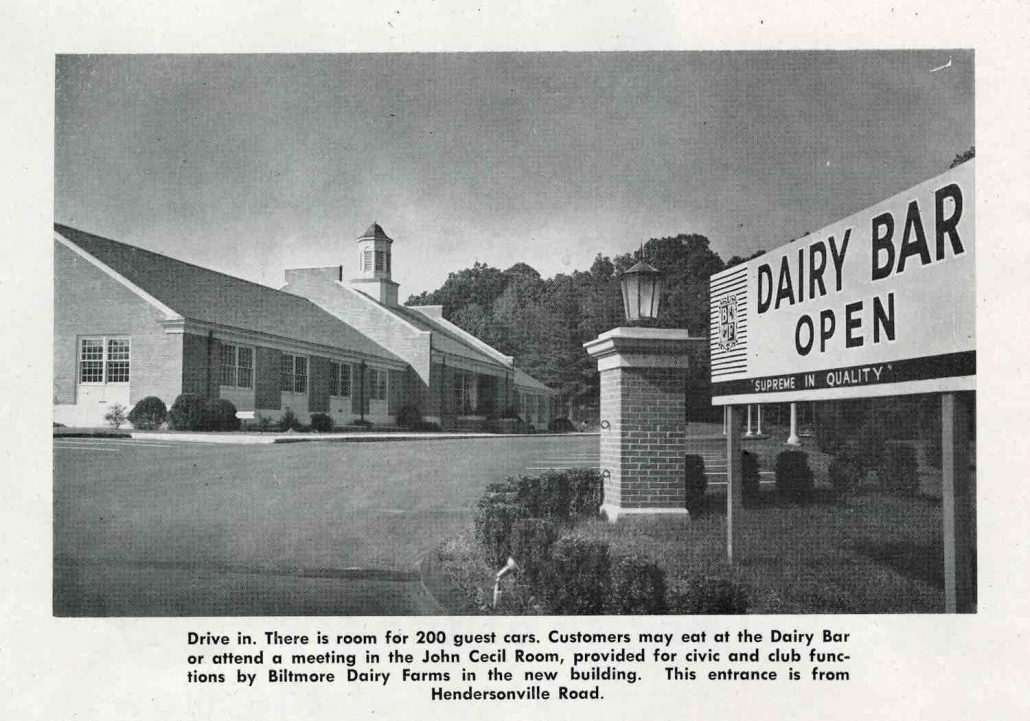

Biltmore Dairy Bar: Pride of Asheville

The Biltmore Dairy was all about fat—butterfat, that is—and people loved it! Luscious, lickable ice cream cones, towering sundaes, and thick milkshakes in pastel hues. They all began with Biltmore Dairy’s high-butterfat milk, which was processed at a bottling plant next door.

From about 1956 or 1957, when Biltmore Dairy Bar opened at 1 Vanderbilt Road, until the late 1990s or early 2000s, when it finally became too cumbersome for the Vanderbilt heirs to operate, this restaurant on the southern edge of Biltmore Village delighted generations of Asheville locals and was sorely missed when it closed. Today, the site is occupied by DoubleTree by Hilton Asheville-Biltmore.

George Washington Vanderbilt is known as the creator of the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, its fairy-tale mansion and gardens. Less well known is Vanderbilt’s role in establishing large-scale farming on a portion of 125,000 acres he once owned there.

Vanderbilt started building his famed dairy herd with 100 Jersey cows and, from there, expanded his dairy herd to some 2,000 head, with perhaps 20 sires, making purchases wherever the pedigrees led. The yields of milk broke records and won prizes.

The original estate dairy building, now a winery, was state-of- the-art when completed in the late 1800s, with central heating for the cows, pipelines cooled with ice to carry milk hygienically from the barn, automated underground waste removal, and more. Vanderbilt’s dairy had a resident veterinarian and a bacteriologist, and the dairy products became known for their freshness and purity.

Thirty years after the dairy bar opened, the economics of milk retailing had changed. The Biltmore Company pulled back its regional reach, then separated the dairy business from the parent company, and finally sold the division to Pet Inc. in 1985. Biltmore Dairy Bar stayed open a while longer as a stand-alone business, but had closed itself within a few more years. ◊◊

Buy local! Lost Restaurants of Asheville is available at Malaprop’s Bookstore, local Barnes & Noble stores, and Biltmore Estate gift stores.

Nan K. Chase is the author of Asheville: A History and Eat Your Yard!, and has written previously about the city’s food history for Edible Asheville.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Nan K. Chase is the author of Asheville: A History and Eat Your Yard!, and has written previously about the city’s food history for Edible Asheville.

THE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.