https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/mckissick-2.jpg

1864

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-08 09:40:002016-11-21 21:44:26Grass Versus Grain

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/mckissick-2.jpg

1864

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-08 09:40:002016-11-21 21:44:26Grass Versus GrainMagic in the Making

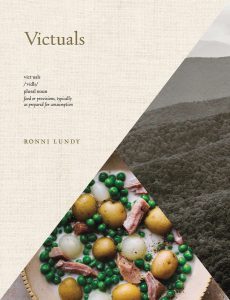

Ronni Lundy’s travels in Appalachian cooking

BY MARK ESSIG

“I have a primal love of these mountains,” Ronni Lundy tells me. In Victuals: An Appalachian Journey, with Recipes, she has written a love letter—perhaps a tough-love letter—to the region and its food.

Lundy has invited me into her home, a light-filled, brick-walled apartment above a shop in downtown Burnsville, North Carolina. She hands me a glass of lightly sweetened iced tea and a dish of cobbler and settles into an armchair to talk food and culture. Lundy has the smilingest eyes you will ever encounter, but her joy is tempered with a fierce desire to give a much-maligned region and its people their due.

Born in Eastern Kentucky, Lundy grew up in Louisville as part of what she calls “the hillbilly diaspora” of Appalachians who left the mountains to find work in the city. She “wandered as a hippy” through much of her adulthood, she says, but has now put down roots in Burnsville, a town she chose to be close to her daughter and grandson. Its proximity to Asheville’s thriving food scene doesn’t hurt.

In her 37 years as a reporter and writer, Lundy has carved out an enviable niche writing about music (mostly country) and food (mostly Southern). In 1994 she published Shuck Beans, Stack Cakes, and Honest Fried Chicken, which became a landmark of Southern cooking. Victuals, released by Clarkson Potter in August, is destined to become another. It is a cookbook and a travel book, filled with portraits of the farmers, chefs, and home cooks who have preserved the traditions of mountain food and transformed them for the 21st century.

“Food was magical” during her childhood, Lundy writes, “because I got to be part of the making.” In Victuals she casts a spell and invites us all to step into the kitchen and become honorary Appalachians.

We can start by pronouncing the name of the book correctly. Say it with me: “vidls.”

To research the book you drove 4,000 miles in what you call a “reliable but rough-countenanced Chevy Astro van.” Tell us about that van.

It’s the only vehicle I’ve ever bought new in my life. I bought it in 2005 and immediately scraped the entire side in what was then the Lark Books parking lot (in downtown Asheville). And then, because I’m a symmetrical person, I scraped the other side going through a drive-through. The van is totally disreputable, but it is totally comfortable and totally reliable.

I wanted to do this book about what is happening right now in Appalachian food, in the context of what the history has always been, and so it had to be a travel book. And it just makes me happy to get in a vehicle and find a radio station that has bluegrass or a really great gospel preacher. Both of those things happen ahead of the beat, in a twirling, swirling way that rhythmically is in pace with driving mountain roads—winding and zipping, a little too fast for safety. I would have these moments when I would come up over a rise, and I would just bounce up and down in my seat and say, “I can’t believe I get to do this!”

How is Appalachian cooking different from Southern?

One of the litmus tests of traditional Appalachian cooking is whether the ingredients could be foraged or grown in this region. And the second test is one of technique. Farm cooking—the cooking of people who are getting their sustenance from the land—tends to favor two methods: low, slow, don’t-have-to-check-on-it cooking—soup beans, cuts of meats with lots of connective tissue, green beans that have beans in them. These are things that could be started in the morning and didn’t require a cook to be paying a lot of attention. The other technique involved foods that could be thrown together really quickly, like biscuits or cornbread—especially cornbread. Cornbread meets all of these criteria. You grow the corn yourself. You’ve slaughtered the pig (whose fat greases the pan). If you’ve got chickens and they’re laying you put in an egg, if you’ve got a cow and it’s giving milk you can put in milk or buttermilk—if not you can make perfectly good cornbread with just corn meal and water and salt.

The question of Appalachian versus Southern is defined by climate and topography. We are Southern. We cook from that same mix of Native American, European, and African influences. But unlike the rest of the south we have winter, and winter requires that we have techniques of preserving that result in foods that don’t exist in other parts of the South or other parts of the country. That includes drying, such as shuck beans (dried string beans) or stack cake, made with dried apples. It also includes fermentation—kraut, fermented corn, fermented green beans.

You spent six years trying to interest a publisher in this book. What changed? Why is now the moment for Appalachian food?

Sometimes there’s not an answer to the “Why now?” question. The wheel turns and a door opens and you can walk through it. Years ago, when (the country artist) Dwight Yoakam’s career was just beginning, I was a newspaper reporter in Kentucky, and we became great phone buddies. We were both working out this thing about being children of the hillbilly diaspora who felt rooted to our Appalachian ancestry. He was the person who said to me, “I followed my heart, and then this door opened.”

That’s analogous to what’s happening now. In 2003 Elizabeth Sims (an Asheville writer, former president of the Southern Food-ways Alliance, and at the time a Biltmore Estate executive) did an event at the Biltmore. She brought in everybody she could find who was interested in Appalachian food. She brought in the kids—I call them the kids—who were starting the sustainable farm movement here, like Walter Harrill (of Imladris Farm) and the Agers (of Hickory Nut Gap). In other places, farmers who were moving in a sustainable direction were learning from books. In Appalachia you could go to the farmer next door, who was 70 years old, and he could tell you everything you needed to know about your soil. You could find seeds that were grown right in your community. The past and the future were existing side by side in the present.

I thought that made a very good story, but nobody else saw it. People kept seeing Appalachia as too poor, too small, too isolated, too obscure. And then suddenly in Brooklyn the kids are wearing Dorothea Lange dresses, and linsey-woolsey britches, and it was like, uh oh, this thing is getting ready to break. It was potentially dangerous, because a lot of B.S. has come out of that. Francis (Lam, the book’s editor) was smart enough to see that this trend had the potential to build a larger audience, but also that there was a story of substance that could further the conversation not only about Southern cuisine but American cuisine.

Anyone who writes about Appalachia has to take on the work of fighting vicious stereotypes. How do you approach that task?

So much of the conversation about Appalachia has to begin with disclaimers. “Actually, no, the region was not isolated. Actually, no, I didn’t marry my cousin.” That’s tiresome. One editor who was interested in the book asked me if we could drop “Appalachia” from the subtitle because of its associations with poverty. Obviously Appalachia is not some fantasy land. We’re like every place in this world right now—a society that has extreme class striations.

I’ve been at this as a professional writer for 37 years now. When I started I wanted to disprove all the negative stories about Appalachia. I have a lot of sympathy for people who don’t want to see any negative stories of Appalachia, whether they’re true or not, because we’ve been so inundated by them. But in the book I’m showing a more complex picture. Appalachia is a culture. The people are an expression of the place, and the place is an expression of the people. It is much broader in terms of the human story than we have been allowed to tell.

You call John Stehling—who owns Early Girl Café with his wife, Julie Stehling—“a great unsung pioneer” of Appalachian food. Why is that?

Neither John or Julie was from Appalachia, but they were very interested in being here. John would just drive around. He would see farmers in the field, and stop and ask what they were growing. This was in 2002. At that point, being a restaurant that provisioned locally meant finding a farmer who would grow arugula for your arugula salad. But John was much more interested in what people around here were eating. What do they grow? How can I bring that to my restaurant? He was using candy roaster squash before anybody. Red clay peas were on their menu. Both he and Julie became very involved in ASAP (Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project), and they used the restaurant to raise money for ASAP, to bring attention to ASAP. They told you where the food was coming from, and they wrote it up on the wall. I know everybody’s doing that now, but it wasn’t happening then.

And then of course you have to mention John Fleer. How amazing that we have both of these men here in Asheville. John Fleer was over at Blackberry Farm (a resort near Knoxville) in the 1990s. He was doing the same kind of thing as John Stehling, wandering around, looking for ingredients, trying to create a cuisine—with a capital C—based on the place that he found himself in. He is the first one who starts putting Appalachian food on the plate in this very conscious and stylized way that demanded attention. Allan Benton (a famed pork curer) and the Cruze family (a Knoxville dairy) and Muddy Pond (a sorghum mill) will tell you that John Fleer is the reason that their family businesses are going into the next generation. That’s pretty extraordinary.

And what generous people both of them are!

The photographs in the book are amazing.

Johnny Autry. Charlotte Autry. They walk on water. I was online, searching for food photographers, and this website for Johnny Autry comes up. First of all, it’s the best food photography I’ve seen. It’s very beautiful, very attractive, but very real—that’s almost impossible to achieve. And it’s not just him, it’s a team. His wife Charlotte is a food stylist and a recipe tester—which I needed, all of the above. So I sent the link to my editor, and he said, “Oh my god, where are these people?” And I said, “They’re in Asheville!” They had been in Birmingham (Alabama). She was on the staff of Cooking Light, and he did a lot of photography, and they had moved to Asheville. So I sent them a note, and I kind of fell in love with them.

If a person picks up your book knowing nothing about Appalachian food, where should they begin?

What month is it?

September.

I would start people with a skillet of cornbread and then get greasy beans—a really good mountain string bean with a bean in it—and make the pot with new potatoes. Fresh corn cut off the cob; Chris Bryant’s Buttermilk Cucumber Salad; and the Busy Day Cobbler with whatever fruit is available.

You write that you come from “porch-sitting people.” It’s fall in Western North Carolina, ideal porch-sitting weather. Could you please explain the proper way to arrange chairs on a porch?

Among my people, you arrange the chairs in a row across the porch, looking out at the road. They could be angled a little bit towards each other, so you could have conversation, but you weren’t in a conversational circle because you were also watching the road, to see who might go by. You did not want someone to walk or drive past your house without hailing them.

Ronni Lundy and her new book, Victuals.

You might also enjoy reading…

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/mckissick-2.jpg

1864

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-08 09:40:002016-11-21 21:44:26Grass Versus Grain

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/mckissick-2.jpg

1864

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-08 09:40:002016-11-21 21:44:26Grass Versus Grain https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/saluda-1.jpg

1000

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-01 13:54:112016-11-04 17:13:27Saluda

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/saluda-1.jpg

1000

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-01 13:54:112016-11-04 17:13:27Saluda https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/sticky-indian-1.jpg

1000

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-01 12:52:182016-11-15 13:55:02Bitter Gamble

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/sticky-indian-1.jpg

1000

1500

sarah

https://www.edibleasheville.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Edible-Asheville-Logo-2.png

sarah2016-11-01 12:52:182016-11-15 13:55:02Bitter GambleTHE WEEKLY REVEL

Sign up for your free handpicked guide to enjoying life around Asheville.

Available weekly from May to October.